Chapter Eleven

The Lander sat lifeless, shuddering in the storm.

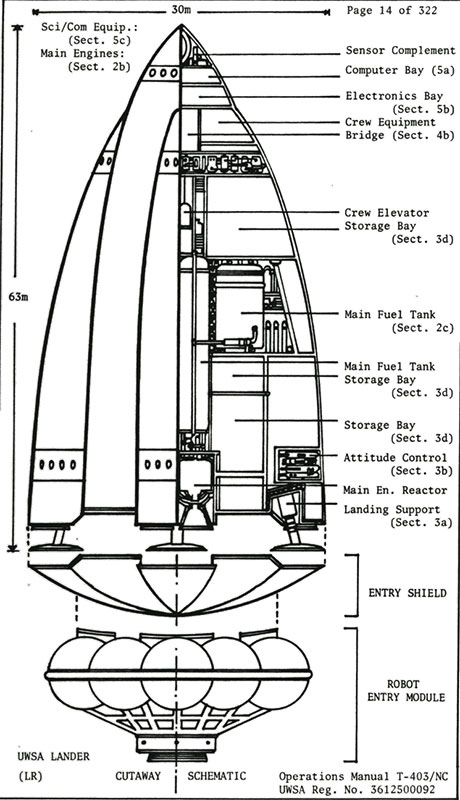

Stavros Ibiá set his emergency lantern on the corridor floor and gave the looted cubicle a final survey. He dragged a damp palm across his brow. He hated to admit it, but he missed the comfortable cycling hum of the air sys-tem. With the power link to the Orbiter down in the storm, the back-up cells were their only remaining energy source and must be conserved. Moments ago, he’d unplugged them and sent them up to the safety of the Caves. Soon, he would follow.

On our own now, he mused. Thrown back on our own resources. Just like the Sawls.

It shouldn’t be so satisfying. Lives were at stake. People would suffer. And no sign yet of the missing. If Clausen and Danforth hadn’t found shel-ter, they’d probably paid full price for their folly already.

Still, it was thrilling. His life so far had been soft, too soft – in the family compound, at the University – while the Earth’s billions labored and sick-ened and starved outside the gates. Removed now from that privilege, he could test his self-sufficiency, his true mettle. It was both harder and easier than he had expected.

He ran through a mental catalogue of the salvaged equipment: items meant to be portable, others he’d spent sleepless hours cannibalizing, still others he must leave behind. The power loss was manageable for now. Once the storm ended, he’d get the emergency solar up and running. But having the com link down was like losing a limb. His fone was his right arm. He was accustomed – they all were – to the ship’s computer providing data, communication, structure, everything. He struggled to recall each emptied niche and cabin, but exhaustion blurred the images and the numbers slid from his inadequately human mind.

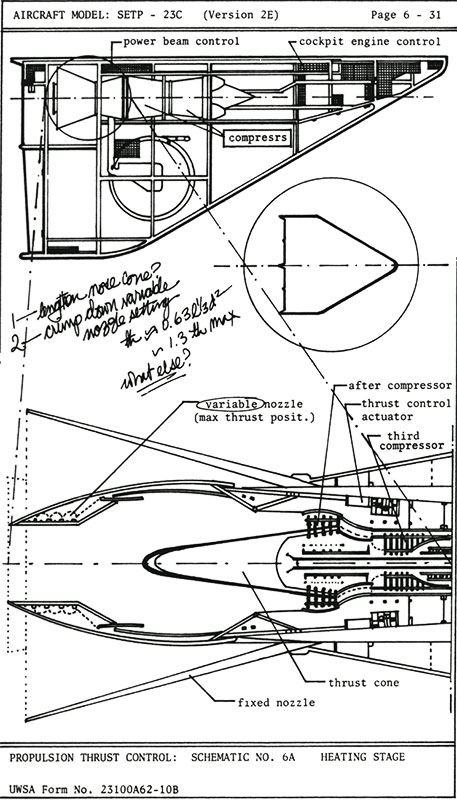

He did regret that Danforth was not around to witness the rape of his precious instruments. Or better still, to be forced to admit that the Sawls had predicted the abrupt weather change with absolute and uncanny accuracy. Perhaps, during those last moments before B-Sled had crashed in the storm – as Stavros was sure it had – perhaps then Danforth had harbored a brief sus-picion, an inkling at least, that he should have set aside his habitual contempt and listened. Stavros hoped he had.

The glare of the lantern stung his eyes. He left it in the corridor and moved into the darkened emptiness of the cubicle. The sounds of the evacu-ation, the general clatter and human voices, the rattle of cartwheels, floated up the central service shaft, softened by distance. The rain beat a hard stac-cato on the outer hull, percussive, regular.

Like a Sawl work chant. Stavros pondered a possible connection.

In the lantern-light slicing through the doorway, the cubicle’s gray walls confronted him balefully. He read reproof in their smudges and stains, re-sentment at being deserted, left behind to brave the storm alone.

You’re not prepared for this, he told himself. First time out of the coc-coon. Who are you to take other people’s lives in your hands?

But in his heart, he wanted it: the drama and the responsibility.

He drank deeply from the clay jug dangling at his waist. The water was sweet relief from the heat of the Lander’s upper levels. He felt it drop to his stomach and spread its chill down into his groin. Exciting, as the storm was exciting, and the smoothly coordinated evacuation of the Lander, The taste of crisis was as real and pungent as the acrid smoke from the cook fires burning in the Underbelly. An adventure myth come alive, all he had dreamed of in his dormitory in the Pyrenees, with its climate control and its spectacular views. Stavros was stunned by the power of these atavistic joys and, innocent of their dark allure, he surrendered to them with a lover’s trembling helplessness.

He took another step into the room, resisting the impulse to search its shadowed corners. In this space, he was an intruder. Danforth’s presence lurked invisibly. His quarrel with the man was mostly a clash of personali-ties. It was hard not to feel challenged by the planetologist’s deep reputa-tion. Measuring himself against the older scientist’s confidence and exper-tise, Stavros found himself wanting, and thus, compelled to sniff out Danforth’s weaknesses and worry them like a terrier. Now, this seemed like adolescent posturing. He wished it was easier to write the planetologist off, but not even Danforth, for all his arrogance, deserved to die in the rain on some alien mountainside.

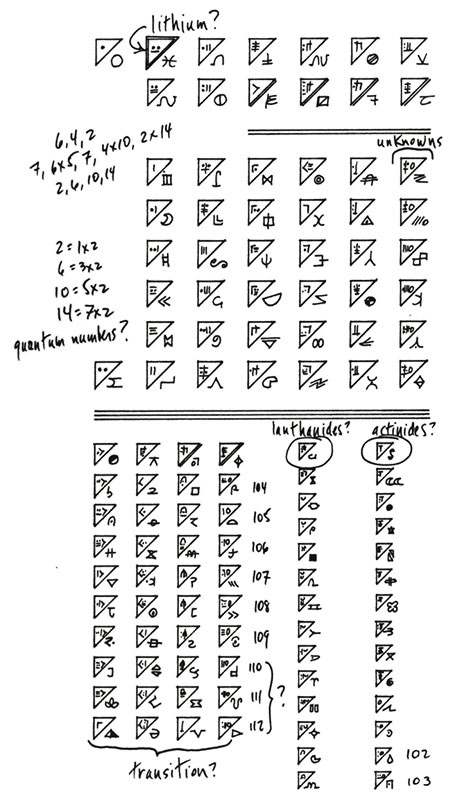

For the loss of Emil Clausen, however, Stavros felt not a moment’s re-gret. They’d all be better off, and Earth would be, too. He had little faith in the prospector’s salvation-of-the-world claims for the new lithium-based so-lar collector that was the excuse for the expedition’s funding. Any addition-al power it might provide would go to the rich and privileged while the rest of the Earth went on burning coal and biomass, and killing the planet. Uni-versity gossip made ConPlex specifically responsible for the loss or adul-teration of at least five alien languages before Terran linguists had had the chance to document them properly. Clausen and his company were a men-ace to all life-supporting worlds.

So Stavros had struggled mightily with his conscience before accepting a post on a ConPlex-funded expedition. But even a wunderkind couldn’t af-ford to turn down a good first assignment, especially a potential First Con-tact. Stavros knew he’d got lucky when Fortune delivered up the Sawls.

He rattled a stray clamp against the shelf of a stripped utility rack. Taylor gone.

“Taylor…dead.” He made himself say it aloud, and the reality of it set-tled around him, like a chill fog. Events were spinning out of control too fast. Stavros snatched up the clamp and surprised himself by stuffing it into his pocket.

Out in the corridor, two sweating Sawls grunted over the last of Danforth’s holo equipment. The lift cage was packed tight. Their comrade-ly debate over where to add to the load was escalating into an argument. Stavros heard the fear in their voices. They were not happy being down from the Caves in such weather.

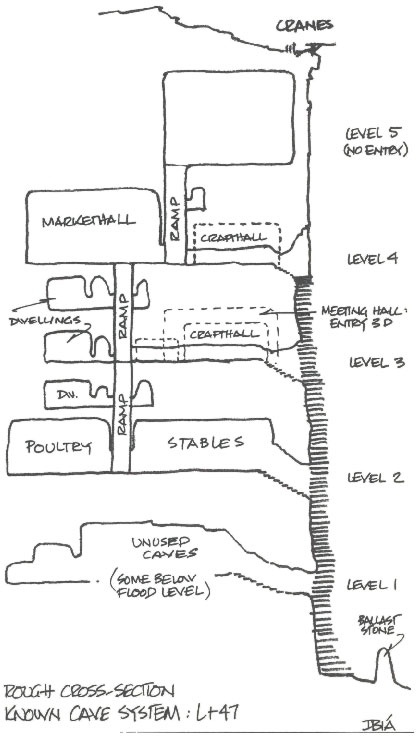

Ropes as thick as his wrist ran up the forty-meter shaft. At the bottom, a giant wooden winch substituted for the Lander’s dead lift system: a Sawl machine hauled down from the Caves to meet the emergency. Storm gusts howled about in the Underbelly, spiraling upward to rock the cage until it banged against its shaft. The hum of the magnetic lift had given way to the groaning music of rope on timber. In the cubicle, the gale circled and moaned, tugging at his hair. Stavros was taken by a vision of ancient ships, of storms at sea. Dizziness seized him. He pressed his forehead to the cool alloy of the racks to settle the nausea, grasping for balance within the tempest of sound.

He was near the edge again, his internal abyss – perilously near – relish-ing the anticipation of terror, recalling the shame and self-loathing that fol-lowed, each time he gave in to it. He shook his head, a lunge for clarity, but was caught by a slap-slap rhythm like the flap of a curtain on a windy night. And then it was too late. Sound billowed around him, carried him to the precipice. He was too exhausted to resist, and why bother, when it was so much more interesting to loose his moorings and slide over the edge. Rain drummed against the Lander’s shell, but he heard the ocean’s roar and the snap of storm-lashed sails. The singsong shouts of the winch haulers echoed up the lift shaft, and he was salt-drenched, hauling at shredded rigging with the men on his crew. Far below, the big machine moaned in its labors – brave wood straining at the upper limits of its strength, but it was his ship’s hull breasting the waves. His body rocked to the taut hum of the ropes, with the creak of canvas and timber. Ecstasy sang in him like a siren.

Like all his moments of transport, it seemed to last forever but did not. It crested and diminished, and he was released. Adrift, reaching for a mast of pain to lash himself to, Stavros slammed his fist against the doorframe, once, twice, yet still swayed off balance as the great ship beneath him rolled into a wave. His bare feet gripped for weathered planking. Another bash of his fist and his mind at last agreed that the deck he stood on was the smooth metal and plastic of a twenty-first-century vessel. But the fright in the faces of the two Sawls at the lift cage told him that this particular motion was not imagined. A tool box slid off the top of the pile and crashed to the floor.

Forty meters down, the winch crew fell abruptly silent.

A cracking like the cry of a rent glacier echoed up the shaft. The Lander shuddered, as the ice beneath it began a slow fracturing.

Stavros sprang toward the lift. He pushed the two Sawls stumbling into the cage, then swung up to wedge himself in on top of the load. The huge knots attaching the lift to the winch ropes creaked right above his head. The cage bucked, dropped precipitately and stopped short with a jolt. The up-drafts whistled. The Sawls hung on with eyes clamped tight.

The lift steadied. Stavros yelled down the shaft for the winch crew to lower away. A chorus of warnings shot upward as the Lander swayed again. The laden cage slammed against the shaft as the Lander settled at a tilt. Stavros renewed his bellowed pleas, waving his emergency lamp as a bea-con. He heard a shout from below, and painfully, the cage edged downward, screeching along the side of the shaft. Down, down, towards the safety of the ground. He managed a grin, brief comfort to his terrified companions on the lift. He raised the light at the entrance to each level passed on the way down, flashing the beam into darkened corners and calling out, making sure no one had been left behind.